A new examination of Apple partner TSMC’s Arizona facility shines a spotlight on how the U.S. bet on domestic chipmaking is colliding with labor shortages, cost overruns, and global dependencies.

Just outside Phoenix, a sleek, high-security facility is taking shape. Known as Fab 21, the site is operated by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) and will soon be one of the most advanced chipmaking facilities in the world.

The microscopic transistors produced here will power Apple devices, artificial intelligence systems and critical infrastructure, representing a significant shift of advanced technology manufacturing to American soil.

TSMC currently makes about 90% of the world’s most advanced semiconductors, nearly all of them in Taiwan. That long-standing reliance is now being reexamined amid global supply disruptions and rising tensions in the Asia-Pacific.

Engineering precision at tiny levels

Inside Fab 21 as reported by the BBC, workers operate in one of the cleanest environments on Earth. Clad in full-body protective gear, they move through sealed clean rooms where even a single dust particle could ruin an entire silicon wafer.

Each wafer takes over 3,000 precise steps to complete and can contain hundreds of chips, each with tens of billions of transistors. One of the first wafers produced at the site featured 4-nanometer chips holding up to 14 trillion transistors per chip, according to TSMC.

These chips are fabricated using extreme ultraviolet light, a process involving plasma generated from molten tin and bounced through precision optics. The machinery required is built by ASML, a Dutch company that supplies the only lithography systems capable of producing these advanced nodes.

TSMC replicated much of its Taiwan production environment in Arizona, but the complexity of the process means the US still relies heavily on foreign equipment, materials and expertise.

Controversies and growing pains

The Arizona plant hasn’t progressed without friction. Construction delays and cost overruns pushed back initial production to 2025, with a second 2-nanometer fab now targeted for 2028.

In 2023, TSMC flew in hundreds of engineers from Taiwan to keep the timeline on track. US labor unions criticized the move, arguing that the company had not done enough to train local workers.

Taiwanese workers brought to the US have reported challenges adjusting to local conditions, from language barriers to regulatory complexity. Some describe long hours and pressure to meet aggressive targets under unfamiliar rules.

Behind the scenes, executives have voiced frustration with US permitting processes, labor availability and cultural differences in workplace norms. Building chips at scale in America has proven far more expensive than in Taiwan, despite federal subsidies.

Officially, Taiwan’s government supports TSMC’s global expansion. Privately, there is concern. Taiwan’s dominance in semiconductors, sometimes called the “Silicon Shield,” is seen as critical leverage in deterring Chinese aggression.

Moving high-end production overseas may reduce that leverage and undermine the island’s geopolitical relevance.

Some in Taipei have warned against letting the US or other allies “hollow out” Taiwan’s tech advantage. Others view diversification as necessary insurance against supply chain shocks or military threats.

Trade pressure and federal subsidies shaped the move

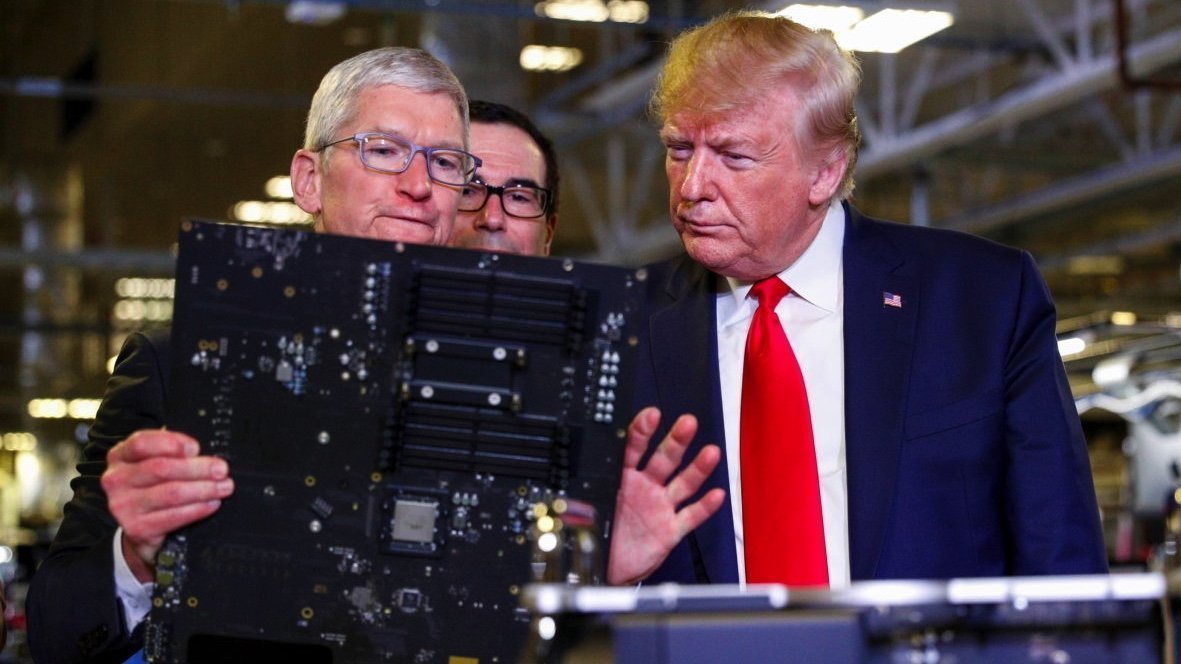

President Donald Trump frequently cited TSMC’s US investment as proof that his tariff threats worked. His administration pushes to reduce US dependence on Asian manufacturing, using trade pressure to encourage reshoring.

Former President Joe Biden focused on subsidies and long-term industrial planning. The CHIPS and Science Act, signed into law in 2022, offers tens of billions in funding and tax incentives.

TSMC’s Arizona project is the largest foreign beneficiary, with $40 billion committed across two construction phases. Phase one is expected to produce chips in 2025.

Despite the political divide, both administrations have treated semiconductor independence as a bipartisan priority. TSMC’s presence in Arizona is the centerpiece of that effort.

Semiconductors are no longer just a tech industry issue. They are now seen as the foundation of economic security, artificial intelligence leadership and national defense.

Trump pushes to reduce US dependence on Asian manufacturing

The Arizona fab is a central piece of the US strategy to localize chip production, reduce dependence on Taiwan and stay ahead of China in advanced computing.

Bringing TSMC to the US gives American firms closer access to their most critical components. It also gives Washington a foothold in reshaping global supply chains around trusted partners.

But the project’s significance runs deeper than corporate logistics.

Strategic chips for the AI era

The Arizona facility is producing chips not only for smartphones and laptops but also for artificial intelligence, cloud computing and defense applications. Companies like Apple and Nvidia have confirmed plans to use chips from Fab 21 in upcoming US-bound products.

Both the Trump and Biden administrations have moved to block China’s access to these technologies. The US has restricted exports of ASML lithography tools and banned companies like Huawei from acquiring high-end chips.

Still, China is racing to catch up. US restrictions have pushed Beijing to go full speed ahead. That’s part of why leaders in both parties continue to push for domestic capacity.

Looking ahead to a fragmented future

TSMC’s Fab 21 is part of a broader reshaping of the global semiconductor map. Intel is building new fabs nearby. Samsung is expanding in Texas. Arizona, already a hub for aerospace and defense, is becoming a critical node in America’s plan to regain leadership in chip production.

But global interdependence will not disappear overnight. Key components still come from Japan, Germany and the Netherlands. Engineers from Taiwan continue to train the US workforce. Even the clean room garments are often imported.

As geopolitical competition escalates, the US faces a delicate balancing act. It must rebuild strategic capacity while staying connected to a global innovation network. The Arizona fab may not make the US self-sufficient, but it’s a foundational step toward greater resilience.